Rooting the Diasporas

plantago (seeds), lamb’s quarters, nasturtium, toad flax, wild lettuce (flower buds), smartweed, and black locust on concrete

The dynamics of gardening always appeared to me as an assertion of power. One can always find parallels between how people treat each other and how gardens and yards are kept. The American Dream is defined by the flawless green lawns bordered by fences. However, as the aesthetic takes hold, a habit of fending one’s own turf with warfare tactics against wildlife and sometimes one’s neighbours also became routine. To keep a status symbol of leisure lush and green, people ironically spend their entire leisure time working up a plan to eradicate the plants they don’t even bother to learn the names of. They are all just weeds, landed and flourished in places where people don’t want them to flourish. Unfortunately, the diasporas seem to be caught in this narrative as well.

When retracing our immigration, my mother always enthusiastically brings up our time volunteering as part of Olivia Chow’s campaign that contributed to an eventual apology from the Canadian government to the Chinese diasporas. Among many non-white migrant workers who came to Canada and built the Canadian Pacific Railway — a part of Canada’s history that the colonial government took sole credit for, the Chinese were quickly deemed unwanted by white Canada when an influx of non-white migrant workers became a part of the fabric. The colonial government introduced the “Head Tax” in 1885 as well as the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1923 on Canada Day. It resembles the stories of many species of plants brought to North America for specific uses by the colonizers. These plants are then deemed weeds and invasive species when the colonizers became essentially “done with it.” Furthermore, countless species of plants native to North America are also considered weeds to eradicate despite being on this land for thousands of years, until the pseudo-wellness industry “discovered” the medicines, then exploited them. There’s always a carelessness in the sense that everything is disposable when it comes to colonial powers or simply “whiteness.” In stark contrast, during the Canadian Pacific Railway construction and later the Chinese Exclusion Act, the Indigenous peoples took care of the Chinese immigrants. They offered aid to the Chinese community in the way that the land would always nourish the seeds that fall onto it without judgements, even when the land itself has been depleted from extraction.

hostas, wild buckwheat

It’s not hard to imagine that I have a deep sense of sympathy towards the interactions between modern humans and plants, particularly the relentless species categorized as weeds, opportunistic yet generous. These so-called weeds send their roots deep and wide, survive adverse conditions, and become places where others who seek food and shelter can settle. What’s created by these weeds is constantly making their environment better suited for life. Dandelions de-compact soils with their deep roots, clovers fix nitrogen with tiny nodules on their roots (in collaboration with bacterias), raspberries spread underground literally weaving the earth together... Soon enough, an unimaginable amount of flora and fauna came to continue making these worlds flourish even though they are not perfect, flourish not in the sense of creating utopian worlds, but protopian ones. However, modernity calls for the hedges to be trimmed neat, trees to be kept straight, flowers to be cut, and fruits to never come to seed. The modern garden is only utopian for those who exert their power to control. All the rest that don’t submit to this power become undesirable, eradicated, and forgotten.

cosmos, bindweed, wild lettuce, lamb’s quarters

Just like that, flora and fauna that don’t succumb to the forces of the modern human lost their names, the same way that people of different traditions became tokenized as Black, White, Indigenous, and something in between but not quite — People of Colour. I grew up immersed in the traditional mythologies of East Asia. In these stories, names are what makes something alive and sentient. A person became a lost soul when they lost their name. A rock becomes conscious when it is named.

My name was reduced to a phonetic version with no connections to its original meanings the minute I stepped onto this land we now call Canada. The only people who refer to me as that name are family, who know my name’s roots. Unlike many people who find comfort in being called their own names, albeit only phonetically, I find it creepy that my name is used in such a detached way. I could easily be someone else, mispronounced. So I did. I invented a version of myself. Little did I know that it would make my life so much easier as if that little detail made others see me belonging here. However, I find myself protective of my birth name. More and more, I would rather people don’t use it unless I’ve had the chance to explain what I know about my name. I always knew that my parents named me after a sage emperor but only recently realized the significance of the name carrying a lot of earth when written traditionally (and fight when written in simplified Chinese). It’s believed that this sage emperor had gathered people to study astrology and established ways of cultivating the land according to their observations of the universe. Perhaps it’s fate that eventually I became drawn to observing the natural worlds despite living my entire life in cities.

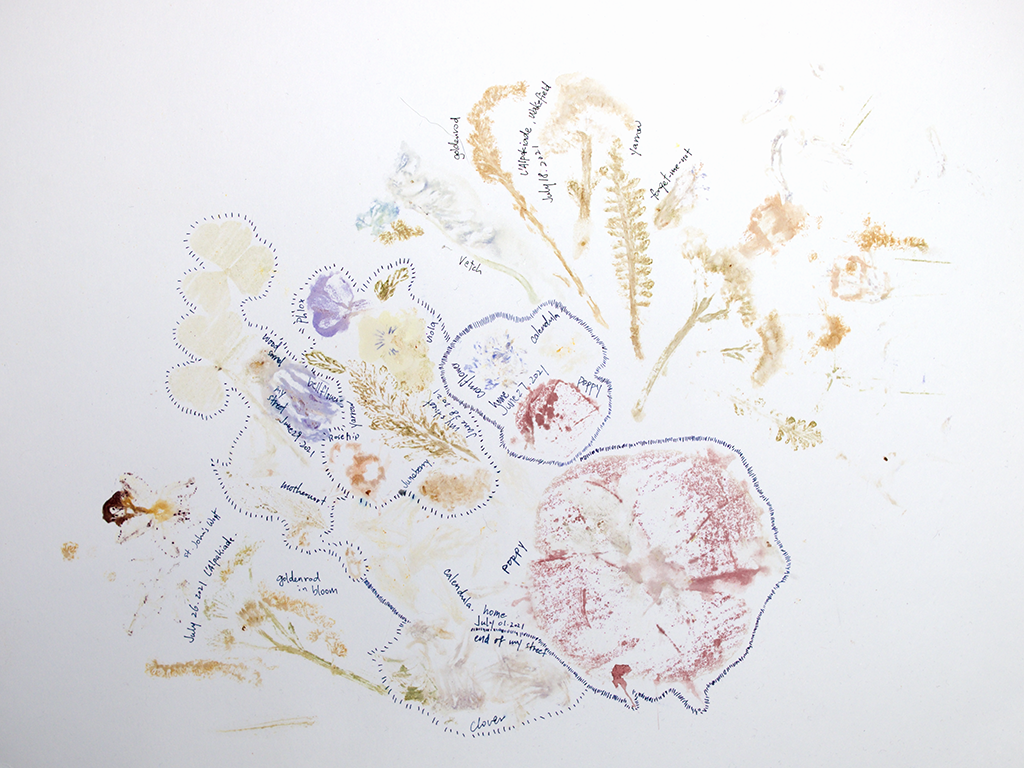

map of my morning walks by plants. to name a few: st. john’s wort, red clover, hairy vetch, poppy, yarrow, godenrod, wood sorrel, comfrey, corn flower…

So I began making an effort to learn the names of the “weeds,” or rather, plants that have lost their names in a modern city. In doing so, I started to see them differently. I began recognizing the medicines, the aggressive-growing ones that carried people through famine, and the prized possessions in people’s gardens but have escaped the fences. Many native species spread fiercely to reclaim territories colonized by industrial monoculture and routinely be cleared out by humans despite aching to repair the land. Many introduced species melted into the landscapes and found themselves living peacefully among species that are native, others not quite kind — they take from the soil and don’t seem to give back (who am I to judge them?). To my surprise, I also found many of them belonging to my childhood on a different continent. For instance, broadleaf plantain or plantago major is a traditional Chinese medicine used to suppress inflammation, native to the Eurasia continent. Here on Turtle Island, the Indigenous peoples call it “White Man’s Footprint” as this plant followed the colonizers to North America and thrived on the disturbed soils where they had settled. Another one, wood sorrel or oxalis, was my childhood favourite. Some sources say wood sorrel is native to North America, but they are truly global citizens with culinary and medicinal histories spread far and wide. Other than its sour candy-like taste, I thoroughly enjoyed lightly tapping on the seedpods and feeling the forces of the tiny little seeds bursting everywhere. Perhaps that’s how the oxalis reached all reachable corners of this Earth wherever the oxalis could survive.

bindweed on concrete

It’s probably unscientific to anthropomorphize plants in western conventions, but I find the stories of weeds eerily human. I suppose this is to no surprise: These plants live close to humans. Some of them migrated with humans across oceans and lands. They inscribed their own histories of the diasporas into the different ecologies as they witness humans uproot and reroot over and over again. I wonder if a plant is ever truly exotic or truly native, the same way I wonder if the diasporas would consider themselves as rooted after generations of being “from somewhere else.”

plantago (seeds), lamb’s quarters, nasturtium, toad flax, wild lettuce (flower buds), smartweed, and black locust on concrete